'Le Supreme Adieu' for 100th Anniversary of the Titanic's Disaster

A poster of a drawing entitled "Le Supreme Adieu" from an

illustrated magazine by the French artist Rene Achille Rousseau-Decelle, which

is held in the archives of the Henryk Wieniawski Musical Society in Poznan,

depicts a young woman dressed in black throwing flowers into the sea from the

deck of a ship. The woman is Henrietta, second daughter of the violinist and

composer Henryk Wieniawski, the sea is the Atlantic where the ocean liner Titanic

sank on 14 April 1912 after hitting an iceberg, and the flowers are in memory

of her husband, Joseph Loring, who went down with the ship.

Rene Achille Rousseau-Decelle: Le Supreme Adieu. Petera Rennie's gift for Archives of Henryk Wieniawski Musical Society.

Henrietta was born in Brussels in 1879 but was living in London with

her mother Isabella and sister Irene at the time of her marriage to Joseph in

1904. He was an American stockbroker who travelled frequently across the

Atlantic on business trips and had decided at the last moment to accompany his

brother-in-law, George Rheims, on the maiden voyage of the Titanic from

Southampton to New York on 10 April 1912. George lived and worked in Paris and

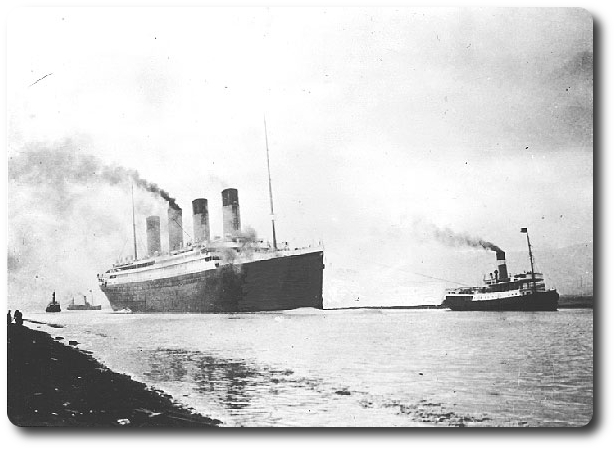

joined the ship at Cherbourg. At 46,328 tons she was the largest and most

luxurious ship of its day, built at the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast,

and carrying 2,207 passengers and crew.

Phot. RMS Titanic. Source: Wikipedia. Phot. Joseph Loring. San Francisco Chronicle, 17.04.1912 r.

Four days into the voyage Joseph and George were in the smoking room

late one evening trying to work out the speed of the ship having followed the

daily postings of the ship's run. A steward advised them to increase their

estimates as the ship had increased speed and they became aware of more vibration.

George later told the court of inquiry into the disaster held in New York that

he had noticed something white passing rapidly across a porthole in a passage

way.This was the iceberg estimated at about 100 feet high (30 metres) which the

ship had brushed against and been holed. In a letter to his wife George

described how passengers were told to put on their lifejackets, which he and

Joseph did, and then they went up on the boat deck to join other passengers and

assist in helping women and children into the 16 lifeboats, which were woefully

insufficient for a ship of that size, and lowering them down into the ocean,

taking an hour and a half to complete. The order had been given that women and

children should get into the boats and men were to stand back, but some men

attempted to jump into them while others slid down the ropes holding the boats.

George witnessed an officer shoot one who tried to get on the last lifeboat

before giving a military salute and then shooting himself.

By now the lifeboats had gone, some of them only half-filled as a result of confusion at the ship's final moments, and some 1,500 people were left on board the slowly sinking ship with no means of escape. It was a cold, starlit night and as George described in his letter people began to say goodbye to friends and prepare to die. Joseph shook hands with George and asked him to look after his two young daughters, Frances and Joan, age 5 and 3, if he should survive and said he would look after George's wife Marie should he live. George returned briefly to his cabin to find a photograph of his wife and then rejoined Joseph on deck. They both undressed to their underwear deciding to jump overboard to save themselves by swimming. The ship was now going down by the bow and an explosion knocked George to the tilting deck where he became entangled in chairs and ropes. He succeeded in freeing himself and urged Joseph to join him in jumping, but Joseph felt unable to and remained on the sinking ship. George who was an excellent swimmer jumped on his own, 15 feet (4.50 metres) into the icy cold water of the mid Atlantic.

When he surfaced he started swimming away from the ship fearing he might be sucked down with it. He saw the Titanic sliding straight down, bow first, with the propellers out of the water in the air, with loud explosions as the boilers were bursting and piercing screams from the passengers pressed against the rails like flies. There was a big whirlpool swirling movement, then silence for a few moments until broken by pleas of help from those able to float. This lasted for about half an hour then all was quiet again. As he swam round looking for a piece of wreckage to hold on to he noticed a group of about twenty people who seemed to be standing knee deep in the water.They were in a half submerged collapsible raft which he managed to get on to and stand shivering with cold with them and balancing

themselves to avoid capsizing the raft. For six hours they endured this ordeal, pushing back people in the water trying to board the raft which was filled to its limit. Eight people died during the night from cold or despair.

In the early hours of the morning one of the Titanic's lifeboatspicked up George and the others on the raft and took them to the Carpathia, the ship which had answered the earlier distress calls from the Titanic. This ship had now arrived at the scene of the disaster after steaming at full speed through an extensive ice field studded with individual ice bergs some 200 feet (60 metres) high to search for and rescue survivors from the water. Only 712 survived of the total ship's complement of 2,207. On arrival in New York on 18 April George stayed for a while at his brother's house recovering from frostbite and wrote the letter to his wife in Paris in which he graphically described his ordeal and that of his brother-in-law Joseph Loring whose body was never recovered. The letter was later printed in a book about the Titanic published in 1981.

Back in London, Joseph's wife, Henrietta, on learning of the dreadful news of the disaster, immediately booked passage on the liner Carmania leaving Liverpool for New York. She was accompanied by her husband's business partner. As the ship came close to the scene of the disaster Henrietta assisted by a stewardess went up on the bridge shortly after the other passengers had gone into the saloon to dinner. There were few people on deck to witness her grief as she threw a large wreath of roses and lillies and handfuls of cut flowers into the water. An account of this private event entitled "Flowers for the Ocean Grave" was printed in the New York Times which may perhaps have inspired the artist to draw his interpretation of Henrietta's "supreme adieu" or last goodbye to her young husband.